Senate GOP shelves health bill, imperils 'Obamacare' repeal

WASHINGTON (AP) - Senate GOP leaders abruptly shelved their long-sought health care overhaul Tuesday, asserting they can still salvage it but raising new doubts about whether President Donald Trump and the Republicans will ever deliver on their promises to repeal and replace "Obamacare."

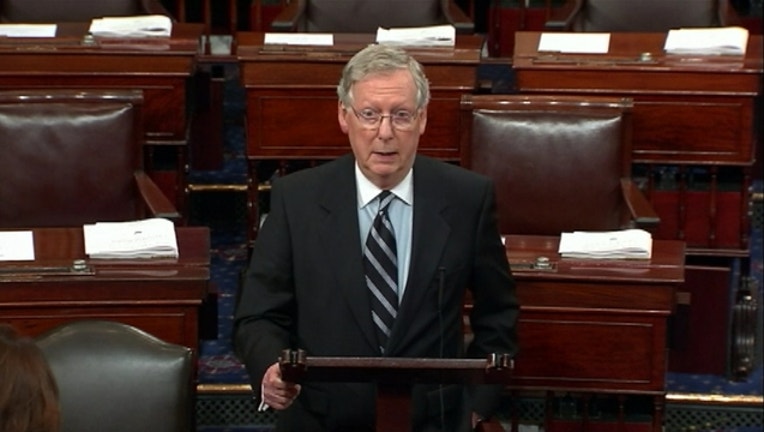

Republican leader Mitch McConnell announced a delay for any voting at a closed-door senators' lunch also attended by Vice President Mike Pence. McConnell's tone was matter-of-fact, according those present, yet his action amounts to a stinging setback for the longtime Senate leader who had developed the legislation largely in secret as Trump hung back in deference.

Now Trump seems likely to push into the discussion more directly, and he immediately invited Senate Republicans to the White House. But the message he delivered to them before reporters were ushered out of the room was not entirely hopeful.

"This will be great if we get it done, and if we don't get it done it's just going to be something that we're not going to like, and that's OK and I understand that very well," he told the senators, who surrounded him at tables arranged in a giant square in the East Room. Most wore grim expressions.

In the private meeting that followed, said Marco Rubio of Florida, the president spoke of "the costs of failure, what it would mean to not get it done - the view that we would wind up in a situation where the markets will collapse and Republicans will be blamed for it and then potentially have to fight off an effort to expand to single payer at some point."

The bill has many critics and few outspoken fans on Capitol Hill. It was short of support heading toward a critical procedural vote on Wednesday, and prospects for changing that are uncertain. McConnell promised to revisit the legislation after Congress' July 4 recess.

"It's a big complicated subject, we've got a lot discussions going on, and we're still optimistic we're going to get there," McConnell told reporters after the lunch.

It hasn't been easy, as adjustments to placate conservatives, who want the legislation to be more stringent, only push away moderates who think its current limits - on Medicaid for example - are too strong.

In the folksy analysis of John Cornyn of Texas, the Senate GOP vote-counter: "Every time you get one bullfrog in the wheelbarrow, another one jumps out."

McConnell has scant margin for error in the closely divided Senate, and the legislation to eliminate Obamacare's mandates and unwind its Medicaid expansion has shed support practically from the moment it was unveiled last Thursday. By Tuesday morning at least five GOP senators had announced their opposition to a procedural vote on the bill, and after McConnell announced the delay several more went public with their criticism.

McConnell can lose only two senators from his 52-member caucus and still pass the bill, with Pence to cast a tie-breaking vote. Democrats are unanimously opposed, and in recent days they have stepped up protests, delivering speeches on the Senate floor for hours and holding vigils on the Capitol steps.

Medical groups are nearly unanimously opposed, too, along with the AARP, though the U.S. Chamber of Commerce supports the bill.

A number of GOP governors oppose the legislation, especially in states that have expanded the Medicaid program for the poor under former President Barack Obama's Affordable Care Act. Opposition from Nevada's popular Republican Gov. Brian Sandoval helped push GOP Sen. Dean Heller, who is vulnerable in next year's midterms, to denounce the legislation last Friday; Ohio's Republican Gov. John Kasich held an event at the National Press Club Tuesday to criticize it.

But the Republicans' own divisions are what has stymied them.

In one illustration, an outside political group run by Trump allies has run ads against Heller and threatens more against other GOP senators opposed to the bill. That infuriated McConnell, who called White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus to label the attacks "beyond stupid." Heller himself raised the issue in the Tuesday White House meeting, Sen. John Thune of South Dakota told reporters later.

The House went through its own struggles with its version of the bill, pulling it from the floor short of votes before reviving it and narrowly passing it in May. So it's quite possible that the Senate Republicans can rise from this week's setback.

But McConnell is finding it difficult to satisfy demands from his diverse caucus. Conservatives like Rand Paul of Kentucky and Mike Lee of Utah argue that the legislation doesn't go far enough in repealing Obamacare. But moderates like Heller and Susan Collins of Maine criticize the bill as overly punitive in throwing people off insurance roles and limiting benefits paid by Medicaid, which has become the nation's biggest health care program, covering nursing home care for seniors as well as care for many poor Americans.

GOP defections increased after the Congressional Budget Office said Monday the measure would leave 22 million more people uninsured by 2026 than Obama's 2010 statute. McConnell told senators he wanted them to agree to a final version of the bill before the end of this week so they could seek a new analysis by the budget office. He said that would give lawmakers time to finish when they return to the Capitol for a three-week stretch in July before Congress' summer break.

The 22 million extra uninsured Americans are just 1 million fewer than the number the budget office estimated would become uninsured under the House version. Trump has called the House bill "mean" and prodded senators to produce a package with more "heart."

The budget office report said the Senate bill's coverage losses would especially affect people between ages 50 and 64, before they qualify for Medicare, and with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty level, or around $30,300 for an individual.

The Senate plan would end the tax penalty the law imposes on people who don't buy insurance, in effect erasing Obama's so-called individual mandate, and on larger businesses that don't offer coverage to workers.

It would let states ease Obama's requirements that insurers cover certain specified services like substance abuse treatments. It also would eliminate $700 billion worth of taxes over a decade, largely on wealthier people and medical companies - money that Obama's law used to expand coverage.

It would cut Medicaid, which provides health insurance to over 70 million poor and disabled people, by $772 billion through 2026 by capping its overall spending and phasing out Obama's expansion of the program. Of the 22 million people losing health coverage, 15 million would be Medicaid recipients.

___

Associated Press writers Ricardo Alonso-Zaldivar, Ken Thomas, Andrew Taylor and Michael Biesecker contributed to this report.